Banksy at Chiostro del Bramante | Artist Date

On an artist date with my son, Ludovico, we got to explore the satirical and politically-charged artwork of the renowned street artist within the Renaissance walls of Chiostro del Bramante at: The Art of Banksy: A Visual Protest. Luckily we went when we did – all of Rome’s museums went into lockdown shortly after our day.

This particular museum is a favorite of mine. Not only is it a beautiful walk from Prati, over the Bridge of Angels, down via dei Coronari, but their shows as of late have had playful themes that feel welcoming and engaging for children. Ludovico is at an age (10) when he has just started following influencers on social media and has developed a taste for certain cartoonists and visual styles. We even figured out that one of Ludo’s favorite YouTubers has riffed on the artist’s nam.

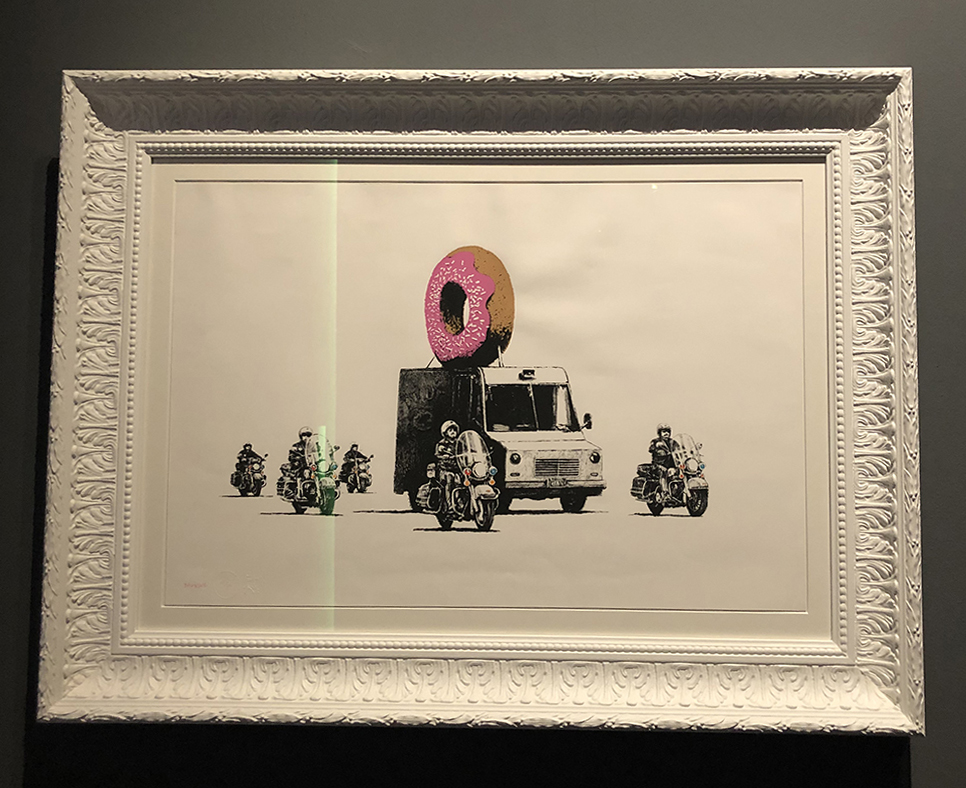

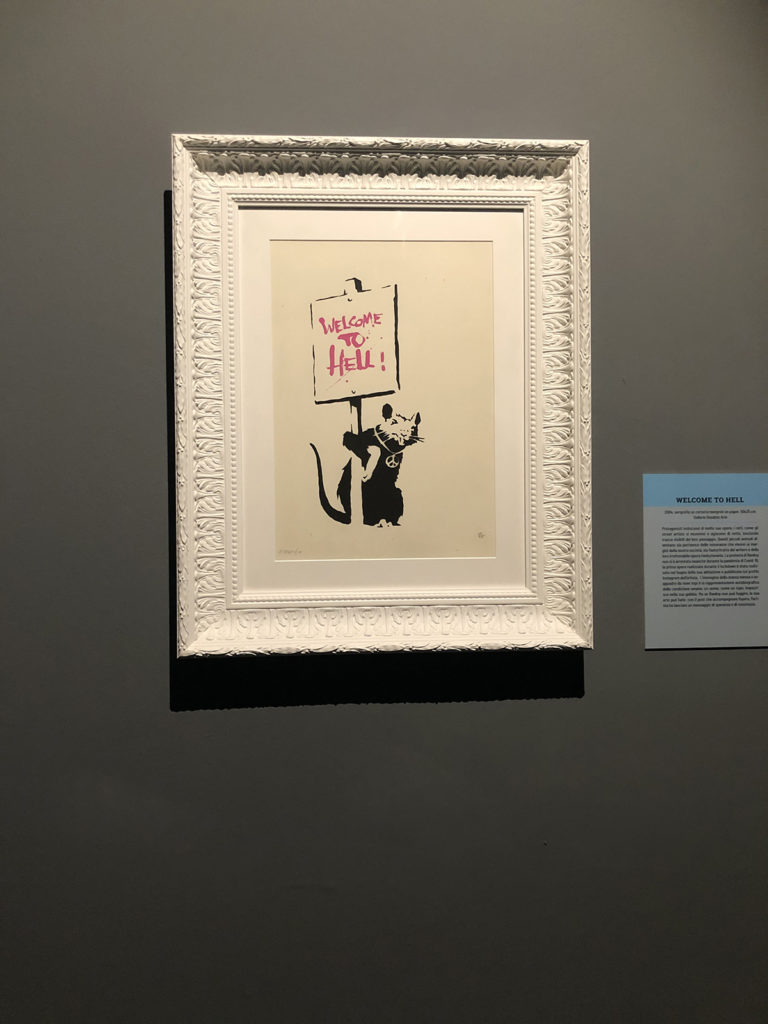

The fun of introducing him to Banksy – and learning more about the rebel artist myself – was chatting about themes of influence and anonymity, which are intertwined with this artist’s “identity”. The images that Banksy creates are deceptively simple. Look closely to discover radical messages about social, economic and political issues. Like a logo, or a universal symbol, his illustrations distill a complex message into a single form.

Many of his works existed first as street art, and the context and placement of the art was an inextricable part of its meaning. In fact, the show and his fame as a fine artist contradict his very philosophy as an anonymous, renegade street artist – powerfully expressed to the public during a Sotheby’s auction. What was a framed illustration became a performance piece, and a phenomenon.

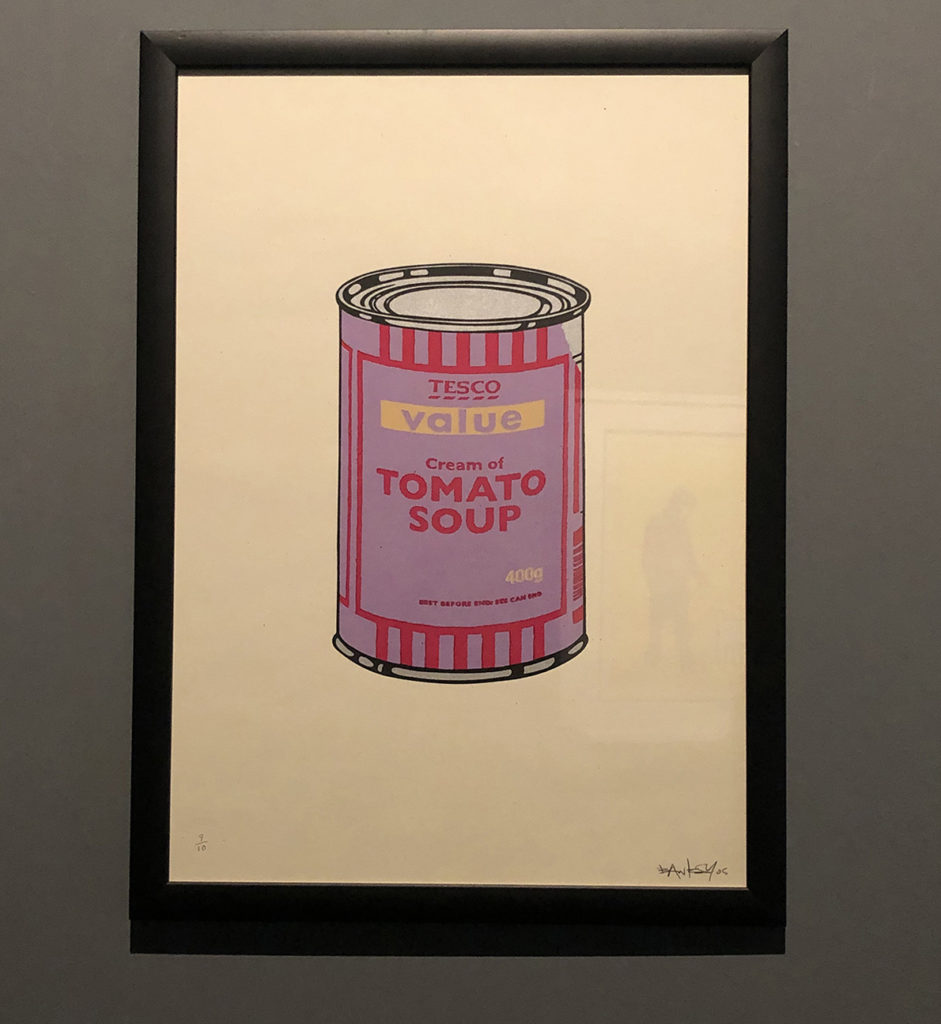

In fact, the “phenomenon” aspect of Banksy is truly riveting, and demonstrates how visual expression transcends cultures and even personal identity. His silence allows his iconic illustrations to speak loudly; the surprise of his work’s appearances create a kind of international game, held across social media channels. One of my favorites is of a discount brand soup can (“Soup Cans: Violet Cherry Beige, 2005) which manages to riff Warhol – or, rather, rip off – while commenting on mass food production and the price of “cheap”. Profound, but so neat.

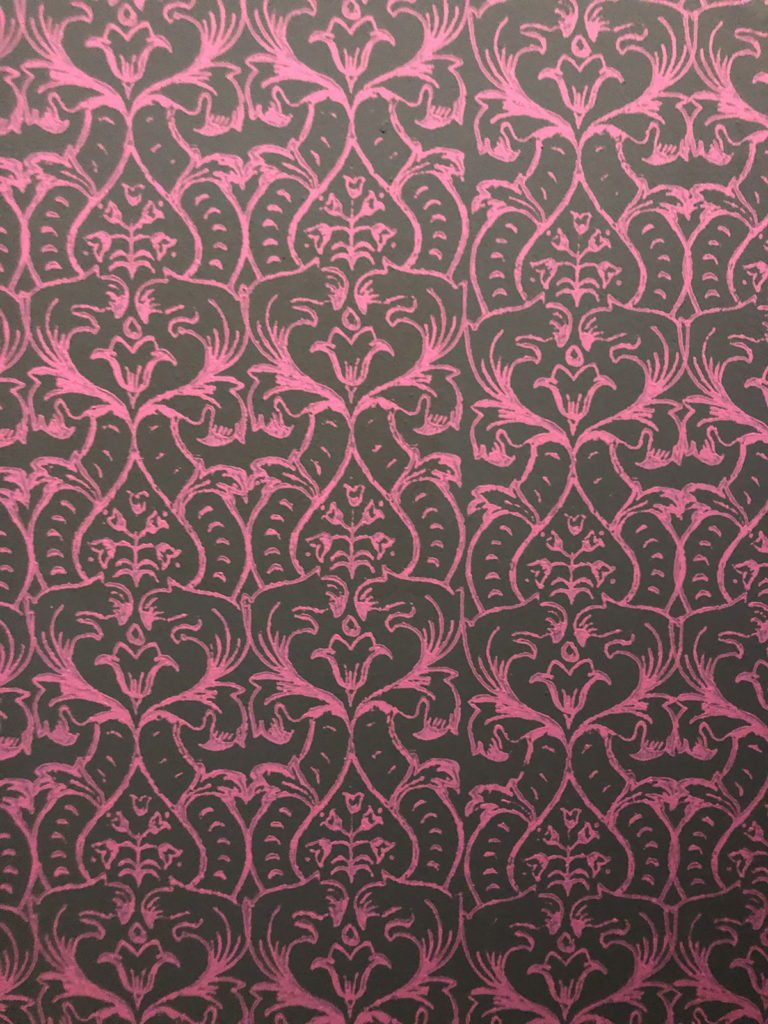

My son and I talked about his art making methods, too – the use of stencils and spray paint, facilitating speedy (sometimes illegal) application of the work in public places. I enjoyed the curatorial choice of using stencil-sprayed backdrops on some of the concrete-grey-covered exhibition walls, though I did wonder if Banksy himself would have approved of the packaged, commercial aspects of the show itself. After all, his imagery lent itself perfectly to printed memorabilia sold at the giftshop – practically irresistable purchases for me as an avid collector of art postcards.

Or maybe that was the point itself – to further diffuse the message of his work, through the captivating, colorful disguise of picture-book iconography.

In the last year, with powerful political and social movements attracting worldwide participation – in person and virtually – it is clear that opinions about how our world is run truly matter. An artist like Banksy leads the way for the non-verbal spread of an idea. If nothing, his art suggests we don’t sit still, but urgently and purposefully, communicate our desire for positive societal change through whatever means we know.